DJ, artist, broadcaster, filmmaker, interviewer, documenter, label owner, original jungle OG pioneer… Ron Samuels has worn many creative caps and had many roles over the years.

Entrenched in b-boy culture since its most nascent chapters in the UK during the 80s – as a breaker and a DJ – he was part of a whole range of movements and collectives that essentially dug the foundations for jungle and drum & bass.

As part of the TNT Soundsystem his selections and style joined crucial musical dots in the build up to the acid house and rave phenomenon. As Rebel MC’s DJ of choice he was the first artist in the jungle fraternity to appear on Top Of The Pops, pre-dating M-Beat’s famous appearance by three years. Resident at seminal culture HQs like Roast and Telepathy, and a key voice on Kool FM, DJ Ron was also the first junglist to record an Essential Mix for Radio 1 and was musical director for the iconic and epoch-defining documentary A London Some’ting Dis. The list of Ron’s contributions to jungle’s deepest foundations run deep and could be listed for days.

After taking a substantial break from music, he’s since returned in recent years as a key voice in documenting the culture and providing space for people to tell their stories. His brand London Something and its filmed podcasts are home to some exceptional conversations with artists from across the scene ranging from Goldie to Nia Archives, they’re not just essential viewing for anyone who’s interested in this culture but also a fascinating insight into all kinds of life stories and challenges full stop.

You can check them here. But before you do, read on for this fascinating insight into DJ Ron’s own life, his memories of jungle’s most formative days and how he remains an essential voice and positive energy in the jungle movement…

You’ve become a really inspiring interviewer in recent years… How you find being interviewed these days?

I don’t mind it. Beforehand I’d look at interviews as part of a promotional strategy that would link to something else I’m doing. One thing that’s different is how I choose very carefully about who I’m interviewed by. By participating in something, I’m validating it. So that’s something I am quite cagey on.

But I have to say, when I started doing these interviews, it wasn’t a big brainwave or epiphany. It was my radio producer who suggested I did a podcast, I then said it should be filmed and we shot the first three in 2018 – Goldie, Rap and Det. They were in the can and I didn’t do anything with them.

Then last year Goldie and I were teasing each other about something and I picked a piece out of the interview and sent it to him to wind him up. He’d forgotten about it and said I should put it out. I hadn’t watched them back for over two years and I remember how I felt when I was interviewing them. Especially with Goldie. He’s such a talker, he’s got a good memory and has had varying experiences, he tells a great story. So I cut my teeth on that interview. I didn’t realise how much until I watched them back.

But up until Det’s one it was still a general podcast. There was no concept of family life and their story, but with Det, it was always meant to be him and Brockie. That didn’t work out so Det and I just did it and we talked about his life. That’s when the concept fell into place… Everyone has a story, everyone wants to talk about how they got to this point and I think that’s of interest to people. Now in this instance I’m telling you my story and you’re doing what I do, which is, by and large, just sitting and listening.

That’s the job of the interviewer. You’re guiding it aren’t you? I think an interview brings out a different type of conversation. Like that one with Goldie. You’re friends and have known each other years, but you still learnt things from him. There’s a real art to that isn’t there?

Yeah you’re right. But you can be too close to someone, too. Me and GQ, for example. We’re good friends, very close. We did an interview which we ended up not completing due to an alarm going off at the location, but in many ways I didn’t appreciate the challenge of interviewing someone who is so close to me. Everyone else is a friend and peer, we have a rapport but they can tell me things I don’t know. With Gary, I knew so much it was almost like I had to act like I didn’t know. Thankfully I’ll get another chance to film his interview where hopefully I’ll be able to do it justice.

I’m slowly moving into areas of talent I don’t know that well. I didn’t want the podcast to be pigeonholed as an old school podcast even though the weight of our subscribers are of a similar age to me, or those who were raving at the time when I was DJing most.

I love the dialogue between the new generation and the pioneers. I speak about this in a lot of interviews.

I hear a lot about this. I can think of a few examples where I felt it, too. Back as far as 2018, I’d speak to younger people who were trying to make the sounds we were making. Thank God this is happening. If young people don’t show an interest in jungle or drum & bass then it wouldn’t exist. Some people come in because they’re interested in the older stuff, others come in because they love the sound of Macky Gee or Bou. Either way, they’re in and that’s fucking great.

Take when I played for Chase & Status and their RTRN II Jungle period. They had a lot of backlash, right? But I was like, ‘Why are people hating?’ Try and analyse it. What is it? Why you going to have a go at people who used to play jungle, went away and want to play it again? If you’re going to do that then have a go at me. I went away for a decade!

I played one particular show with them in Liverpool and an older guy was chatting to me. He explained how he’d heard someone say, ‘What’s jungle?’ in the queue. From that point I thought, ‘Okay, if they’re introducing a new generation of fans to jungle then great.’ Without the young people we wouldn’t have a scene. We need the scene to follow on and keep it going. And I do think there was a lot of sanitising of the scene, which is something I won’t get into too much, as I do think we’re gathering some balance now and that balance will continue until it’s a global balance.

Absolutely. I want to go back to when you were younger… Those stories of you mixing and Rodney P spitting in your bedroom. Those formative years. London Posse started here. Rebel MC started here. DJ Ron started here. Take me back…

It was an interesting time. I don’t remember where I knew Rodney from or how we got to know each other. I was part of a Covent Garden entourage. We were breaking as a group called the Wizard Force which was the youngers for Popping Wizards. During this I gravitated to the music side and Rodney and MC Mello would come over. I’d cut up records and they’d rap. I got fond memories of that time.

Then my brother had a soundsystem called Romancers Delight. Playing for them was the first time I ever played on a sound system. On that night they played with TNT who went on to say ‘Come and play for us.’ Something my brother encouraged. They had the biggest sound in east London and were very progressive in how professionally they presented sound system culture so I joined and became their lead DJ. That was the beginning of me being DJ Ron.

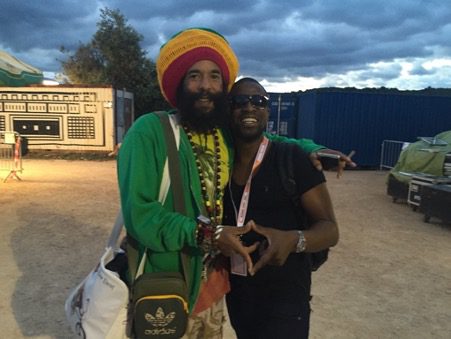

We did a lot of shows, including one in Stamford Hill which was put on by Rebel/ Congo Natty, who was Mike West at the time. Mike and I started to get to know each other from there. He was a visionary even back then. He wanted to be a rapper, he wanted to go to the studio, it was quite an alien concept for us but we did a couple of things.

Like the Eastenders thing!

Yeah. I thought it was good, but of course now it makes me laugh. After that I wasn’t in the studio for a while but Mike persisted. Then one day he came round and said they were touring and he wanted me to DJ. We were meant to meet up but I didn’t turn up but he came back again and said he’s doing another tour. This time I did turn up and that’s when DJ Ron and Rebel MC came about.

By then rave had taken a hold of the country so my music selection was changing. I had no interest in the raves whatsoever but a friend – DJ Connie – gave me a bag of acid house records and I started playing around with them and buying some more. I was playing mostly because of Rebel but slowly I was getting booked on my own, too.

I’ve spoken a lot with Congo and listened to a lot of Rebel MC material recently and Black Meaning Good is a jungle blueprint. Lyrically and vocally he really embraced his Englishness. There was lots of breaks on there, too. An early jungle schematic.

Definitely. I think a lot of what Rebel did for jungle has been overlooked. He’s evolved as a person over that time. He’s not the same person who was giving me these dubplates – the biggest records of that time. What he did for this business, because of the person he’s become, it’s not been respected. It’s interesting, I went to see the documentary Nothing Compares on Sinead O Connor and it made me think of Rebel because she’s a radical. Radical is seen as a bad word but Sinead stood up for what’s wrong and over time she’s been proved right. Rebel was the same a lot of what he said was forgotten because he was seen as the entertainer and not as the boundary breaker.

He told me he had to burn Rebel in the fire and rise up to become Congo Natty because of that. It’s interesting you mention Sinead. I found it mad that her and Marlon M-Beat developed a friendship during that time.

I didn’t know that but it doesn’t surprise me. They were the same ages, in the same situations and had been brought up in similar backgrounds. They’re humans, it’s the fans who see them as popstars. They’d probably be relieved to see each other in the green room.

It’s also very interesting about him burning Rebel to come back as Congo. He could have made number one hits because of how popular they were in the scene but he didn’t want to. He was instrumental in this whole thing. Like I said, a real visionary.

Was there a real key ‘wow, this is becoming something’ moment in jungle for you?

Yeah it was Roast. Back then it was Sunday Roast, in Turnmills, Clerkenwell. My friend Andy had said I should play more breaks around this time. I remember saying, ‘Nah, you’ve got to mix it up, you need some 4x4s’. Anyway someone invited me to Roast and they could get me a play. I arrived with my records and the person disappeared! I didn’t know anyone there, I didn’t know the promoters but it turned out that a DJ didn’t turn up so I was able to play.

I read this! Then the next DJ didn’t turn up…

That’s right. And the longer I played, I was running out of records. In the end I had to just play breaks and that’s when it blew up. They made me resident and Roast became one of the biggest events in the jungle community in London. It was the spot and everyone knew about it nationwide. As I was a resident, Rebel had a place to feed his music to. It was a very progressive time and that’s where everything changed.

And you were resident at Telepathy, too… Another seminal place where this music incubated.

To me there were two Telepathys, two eras. The first one was when Eastman’s dad was a partner. That was Marshgate Lane. I did the odd gig there but the main one that people mostly recall was down by the motorway, down by the A12. That’s where they had their longest standing events. I think it might have even been weekly or fortnightly. It was like a Fabric of our time now. Not as a big size-wise, but regular.

That’s where a culture happens, community forms and tunes can be broken and anthems can be made.

That’s very true. And it’s a shame that there isn’t a regular event like that. It’s not as easy to break records – it has to be very special and different and someone needs to go ‘I’m going to play this irrespective if you’re not dancing’. A good example are the records Shy pushes. They’re not normal, they don’t fit in with everything else that’s being played but he’s going to play them anyway. And this brings the balance that I touched on earlier. You’re introducing a different sound within the same environment – you keep on hearing it, keep on hearing it and eventually it doesn’t sound different and this is what small clubs used to do. I love a small club – a little 300/400/500 capacity. I think everyone does.

Totally! You mentioned Eastman and obviously Kool was huge for you and another place where you could break tunes and set people up with the sounds you were playing.

Yeah it’s interesting. In speaking to Det and Brockie, I didn’t remember it how they remembered it. I saw it like Kool was doing their thing and I wanted to be part of it. Brockie said when I came to the station I brought it up a level. It was very complimentary to hear that but when I think about Kool I think about how it touched so many lives. People come to me and speak about how important it was to them as a ravers and the ravers’ story hasn’t been told. The impact of Kool was huge. It was the soundtrack to the beginning of the night, or the soundtrack to what’s happening tomorrow night.

Or the soundtrack of coming home or being too young and waiting to get old enough to get to the raves.

Yeah exactly!

So during this you helped to make the documentary A London Some’ting Dis. That happened in real time, documenting what was happening and capturing that moment.

Yeah you’re right, it was like Bombing and how that captured the graffiti scene in real time. Capturing a moment while it was happening. Rachel, the director, is still a good friend of mine. A young white girl from the suburbs studying at a film school, got caught up in the jungle scene and wanted to do something. I think it was Moose who introduced me to her and she came to my office in Goswell Rd and I became the access for her. As you know, access is the hardest part in a way. Even now. The access helped her to make the film and she asked me to curate and be musical director for it. I think it’s become something of an enigma because there’s no clean copy anywhere. You can only watch clips here and there online.

You studied film much later on and you do what you do now. Did this sow the seeds?

No not at all. I wasn’t interested in film at all back then and it didn’t lead me down that path. What opened my mind was when a friend of mine produced a film called Dead Man Running. It had 50 Cent in it and a few other names. I thought, ‘That’s interesting. How did he do that?’ Then a while later I was abroad. I wasn’t in the scene at all, I was on a downward spiral at the time and there wasn’t a lot of good happening in my life. By my own design.

Then, cutting a long story very short, I was in America at the time and I had what I can only call devine intervention that I should study film. After a series of more serendipitous happenings I went on to study. At some point in the last year of studying I was at a friends house and she’d just helped make Rinse legal. We got talking and this led to me working at Rinse and helping them build their YouTube presence. Between my colleague Brennan and I, we pioneered a lot of things that In many way that led me to coming back, although I had no intention of being DJ Ron again.

You’d left the scene for a long time. Was it the sanitisation of it that led you to leave. I read you’d had an accident too…

Yeah I had an accident, but that was a catalyst which made me think about leaving. I went into business for a long time, setting up a lot of labels to release more regularly and more broadly. I’d felt the DJing boat had sailed, a lot of parties I was playing were no longer going ahead, the music had got quite aggressive and I could see there was a deliberate attempt to change the scene I had helped to build. I was like, ‘I’m out’.

What pushed that change? The commercialisation? Major labels? Promoters? Authorities? Media?

There were just less and less raves where people of colour would go to and the more that disparity grew the more I thought, ‘Where do I fit in?’ Some guys were able to adapt to different sounds but I was faking it. I was playing records I didn’t like. So eventually I left. Every now and again friends would be like, ‘It’s coming back round, you need to get back in it. Come on!’

Friends like Gary GQ?

He knew how I felt but guys like Zinc, guys like Moose would always do what they good to get me more into it. Then I was at Rinse and I was asked to play, I was like ‘Nah I don’t do that anymore’ but after some persuasion I did it and I enjoyed it and slowly I got back on the radio.

Then the film stuff really started to build up and I wanted to focus on that more so I still kept the music on the side but I learnt to love the music again and that’s where I am now. I can’t listen to every record I’m sent and if I’m not doing that, then I’m not really on it. The amount of focus and energy I put into film every day is a lot greater. So that’s the balance as it stands right now.

I love that. It keeps bookings special too

That’s right and now I’m into it, I say that fondly. I’m into the complexity of it. I love how there are people in Russia are making jungle and drum & bass .There are people everywhere on the planet and you listen to the musicality and you can hear these people are embracing all of the facets of jungle and drum & bass. Globally. That’s incredible, considering us kids from the inner city turned round and developed this thing that is now global. Thanks goodness for people who’ve helped move it forward by sticking to their guns. Thank goodness for people who’ve developed new types of jungle drum & bass. And I think its great that there’s a lot more ‘live and let live’ ethos among us. There was a point where it was like, ‘It should be like this! You can’t change it!’ And I think we’ve eased back off that attitude and I’m a lot more optimistic about the future.

I get why people were so protective though. It was so special that people were scared to change that…

We have experience in it now. We never had an experience in it before and there was a worry that a change might affect us. Now we’ve had this experience, across the arts in general, people are being creative and leaving things to blossom. To be able to create a track from just an idea – that raw concept makes you think, if you can do that with a piece of music then why not a film? Or a piece of writing or content? That raw sense of an idea is very strong right now and I also like the fact that the other music genres – especially garage and grime – pays respect to jungle. The heads of those movements speak about jungle as being what brought them to where they are. That’s an honour.

What a legacy!

Do you know what I mean? And there’s still more to come.

Tease us…

A lot of things I’m signed under NDA and I can’t speak about but there’s some film projects I’ve been working on for over two years, others that have literally just started. Also I’ve started playing with production again and there’s a remix coming very soon.

Wow. DJ Ron is properly back!

I don’t know about that. But yeah, someone asked me to do a remix of them and I thought they were joking or there was a mistake but there wasn’t and that’s coming out. I told him I haven’t made a record in 15 years. He told me one of my earliest records was the first he ever bought so that endeared me to do the remix. That’s not what the future holds for me… Just an anecdote on what’s happening.

Who’s the remix of?

It’s for Max Cyrus’s new label Max Cyrus Music a record called Mirrors featuring Omar and K Triggz. It’s really interesting and I think it’s out before the end of the year but hey, there’s lots of things happening right now. It’s an exciting time…