‘Niet voor één gat te vangen’ – as the Dutch say, meaning: ‘Not to be caught in one hole’.

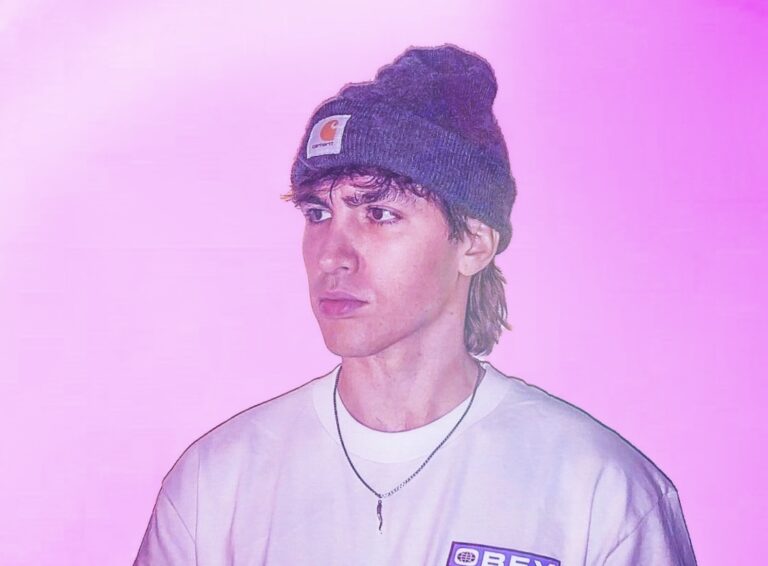

Thys (Thijs de Vlieger), one of the three founding fathers of the now defunct Noisia, is dead set on defining this new chapter in his career on his own terms. So much so, you might call ‘steering clear from expectations’ his new signature move.

Saying he’s chosen the path of least resistance, read: sticking to the old guns – would be far from the truth. The transition into a whole new chapter of the creative journey is rather expansive.

Recently he’s been teasing with singles from his upcoming French house EP Le Thys on Fool’s Gold Records that will hit the (digital) shelves on 30 May, featuring a collaboration with none other than UK garage legend Daniel Bedingfield, called Get Some.

As for the next ongoing collaborative works: VIER (Machinedrum x Thys x Holly x Salvador Breed) is poised on rewriting the rule book on mind-melting sound design in the realms of bass music.

And before you might ‘catch’ him at Glastonbury this summer, in the weekend of 24 May there are concerts planned in Groningen, where Thys will be playing a church organ live – which promises ‘a meditative experience’, according to Thys, one he’s been working towards for quite a while.

So what also to look forward to in this longread interview? Heartfelt anecdotes from a veteran who has seen it all and returned, but with a transformed view and approach. Plenty of comparisons on the good and bad, so to speak, with meticulous weighing of the nuances, while touching on the past, present and future.

And yes, Thys neither is shying away from sharing practical wisdom for upcoming artists who want to expand their perspective. So without further ado, enjoy.

Looking back, what was the first piece of music you worked on after the Noisia farewell tour? What was that process like?

The year 2022 was a period of immense personal upheaval. I lost my father, we undertook the Noisia farewell tour, a five-year relationship ended, and our manager announced his departure from artist management altogether. It was, to put it mildly, a huge mess.

I remained productive musically, but focus was elusive. My approach was simply to live through it, to feel everything, without excessive planning. The priority was navigating the intense emotional rollercoaster of that year and simply making it through.

So being able to channel that turmoil creatively, was it part of the healing process in a sense?

Yes, definitely. In 2023, I released “Shoulder to Shoulder” on Vision. That album incorporates work made before, during, and after that tumultuous period. That release also marked a point where, after a few months post the final Noisia shows, I truly realized my willingness to put in the necessary work to continue DJing. The COVID lockdowns had been particularly difficult; not being able to DJ led to a genuine depression. I was acutely missing the highs of performing, the feeling of doing something that mattered to others and therefore to me, and the vital social and energetic stimulus the shows provided.

The farewell tour solidified this: I needed to keep DJing for my own sanity. My adult life, my emotional equilibrium, had been built around a balance of stimuli and emotional states, including the adrenaline and endorphins of doing shows.

The nervousness before a performance, while unpleasant, becomes almost addictive, because it underscores the significance of what you’re doing. This realization propelled me to create a club EP. I felt done with predominantly releasing experimental or unexpected music for a bass artist.

My focus shifted to making club music that would get me booked in clubs. However, I was also clear that I didn’t want to be confined to the drum and bass stage anymore. I needed a few years of clearly signaling that I wasn’t interested in merely retracing Noisia’s steps.

While I’ve started making 172 BPM tracks again – still love the tempo – I want to avoid being automatically pigeonholed back into a space I had to leave. Playing a purely drum and bass set on a festival stage now would feel limiting, almost like dumbing myself down taste-wise.

This is why I initially focused on 130-140 BPM tracks. Even before the Noisia farewell, during COVID, I released the 160 BPM “Brand New Drop” remix (for Addison Groove), which was an early indication of my desire to make club music as Thys.

After the tour, I intensified my production of club music, taking it much more seriously and initiating collaborations with artists I admired, like Nikki Nair. Most of that work is now out, and I believe the musical statement I intended to make is quite clear.

How would you define the identity you’re carving out for yourself as Thys?

When I talk to professional marketing people, I often express my struggle with clear self-identification, mainly because a fixed identity is precisely what I wish to avoid. My goal is to be “hard to market,” to have the freedom to pursue completely unrelated musical projects.

They are all music, of course. For instance, I’m currently involved with a new bass music collective reminiscent of Noisia, but simultaneously, I’m crafting a French House EP, composing for a church organ, and composing music for a film.

These wide interests have always been a part of me. Noisia provided an outlet for some, but its strong momentum in one specific direction often meant that personal explorations, perhaps not fully shared by the other members, couldn’t always be integrated.

So, if I had to define myself, it would be with a touch of cheeky laziness: undefinable. I see myself as constantly changing, transient, always in between states, with curiosity as my primary guide, leading me to new territories.

That’s the essence of what I want “Thys” to represent. However, I’ve recently found myself being more consistent, particularly in acknowledging my profound love for DJing. I feel a strong urge to release a significant amount of club records to clearly signal my commitment to DJing. It’s an aspect of my life I genuinely don’t want to lose.

Compositions and more experimental projects can be pursued more independently. If an idea for an ambient record or a church organ piece comes, I can simply act on it. But DJ shows are different; they require a distinct profile – an awareness in the scene that this is something you actively do.

Is that also about really having that connection with the audience?

Absolutely. When I release a song on Spotify, a connection with the audience technically exists, but it doesn’t evoke any real feeling in me. Spotify statistics tend to be a source of negativity for me. High play counts are good, but I don’t feel them. Low play counts, conversely, bring a sense of “shit, it’s not working.”

DJing is entirely different. Even with a small audience, if the atmosphere is right, I can look into people’s eyes, hear their reactions; sense their presence in a more visceral way.

Most importantly: I witness their joy, the direct impact of years, even decades, of my effort, culminating in their experience on that specific night. That immediate feedback, that shared joy and the profound sense of purpose it instils – the feeling of doing something that truly matters to others – is incredibly difficult to replace in any other aspect of life.

As for your motivation in the studio today. Is having the full freedom to explore now what motivates you?

The interesting thing is, I had that freedom within Noisia too, but it always felt secondary, like a side-quest that was hard to take with complete seriousness. Psychologically, it felt dwarfed by the sheer scale of Noisia. This made it challenging to dedicate myself fully to other personal projects when Noisia was so all-encompassing – it was the primary income source, we had a large team to support, and immense responsibilities to ourselves, Nik, Martijn, and even our families.

The weight of Noisia then was far greater than ‘Thys’ now. So, with the dissolution of Noisia, it wasn’t just the falling away of that immense responsibility, but also the shedding of the internal feeling that Noisia was, by default, creatively and artistically more important than any fleeting curiosity or excitement I might have had for a solo exploration.

I simply couldn’t manage to give my personal artistic explorations the serious attention they deserved back then. Now, as a solo artist, I’ve been compelled to take myself, and my work, much more seriously. That shift was essential for me to arrive where I am today.

Is continuous reinvention a necessary thing for long-term artistic survival and satisfaction, or a personal choice, especially having been on the bleeding edge for quite a time?

For me, it’s unequivocally a personal necessity. From a career perspective, it would likely be far easier if I could remain passionately excited by a single genre or style for years on end. That consistency would simplify many things. But my nature thrives on variety. Curiosity is my core driving force, and curiosity, by its very definition, demands change and new experiences.

Some individuals can maintain a deep curiosity within the same subject for extended periods. I do find myself revisiting areas I’ve explored; I don’t just touch on something once and abandon it. I might do another EP in a genre or another project within a certain style, but only after my curiosity has first led me to something new that I feel compelled to actively explore and create with.

I’ve learned to go with this flow, all the groundwork – the studying, exploring, and understanding of my preferences within that context – is then readily available. I can then pick up right where I left off, often with a fresh perspective.

What’s the biggest psychological barrier to overcome when you consciously decide to shift your artistic direction?

The primary psychological hurdle is knowing you’re likely to disappoint some people. Fans often want what they already know and love from you. When you offer them something different, you’re essentially seeking out those within your existing audience who will embrace the new, while accepting that many will express a preference for your older work.

Disregarding some of your audience’s explicit desires is challenging. It’s perhaps easier for me than for some other artists I know, but it’s by no means easy. Deliberately disappointing people, even in pursuit of your own artistic path, is a difficult thing to do.

However, I am acutely aware of the alternative. Because if I don’t follow my artistic curiosity, and force myself to stick to one thing purely for career stability or financial reasons, I know I wouldn’t be happy, and eventually, I would quit making music altogether.

That’s a certainty for me. So, faced with that choice, pursuing my work in the way that I believe, will allow me to continue sustainably.

If there’s an audience interested in an artist like me – someone who is constantly evolving – and while I can make a living by being authentically myself, not someone who others want me to be, then I can keep going.

If I were to constrain myself to fit others’ expectations, I might be playing more shows and earning more money in the short term, but I’d inevitably reach a point where I say: “This isn’t what I want,” and would quit.

Ultimately you risk becoming a product with a shelf life. Does this relate to balancing commercial reality and staying true to your vision?

Yes, it does. I am, of course, in a very privileged position due to a combination of luck, the rewards of past hard work, talent, and circumstance. I’ve worked diligently to get where I am. This privilege allows me certain freedom.

Observing the current struggles within the music industry, I recognize that things aren’t easy, even for me. I’d love to play more shows, but booking international DJs, especially those not heavily active on Instagram, has become very expensive. It’s a significant risk for promoters to invest in an artist based purely on their music if they don’t also have a strong social media influencer profile to aid ticket sales. The old ways of promoting; a poster, a flyer, word of mouth about how incredible an artist’s music is; they no longer have the same impact.

There was a statistic recently about a majority of artists believing it’s more important to be a social media presence than the actual music itself.

That is the unfortunate reality we’re in. My privilege allows me to continue making music my way, despite this. However, for long-term financial sustainability over the next 10–20 years, I will need more shows, or better-paying ones. The overall state of the music industry is genuinely tough. Many artists are forced to accept unfair payment terms or work that doesn’t provide a sustainable living, a stark contrast to a decade ago.

Numerous clubs are closing because the financial risks outweigh the diminished rewards, largely due to inflation. Most people feel financially strained, with less disposable income for things like club nights and festivals.

The statistic about 60% of Coachella tickets being bought on credit, with payment plans and interest, is a telling sign. The economy has shifted, making a career in DJing increasingly a luxury. However, I believe the core need for what DJing and club culture provide – community, a shared experience, the collective journey of a good DJ set – is primal and enduring.

Humans have engaged in communal music and dance for millennia. This fundamental need won’t disappear. So, while I don’t think DJing itself will die, “career DJing” might become an even more privileged position, not accessible to everyone.

I do worry about my future income from this perspective, but again, my past success affords me the ability to invest in myself and manage a period of breaking even. My deeper concern is for the health of the industry when young, emerging artists cannot afford to take the kinds of risks we could 20 years ago.

What advice would you give to young artists struggling with the current state of affairs?

My primary advice would be to focus intently on the joy of creation itself. Cherish the process of making music, and also the satisfaction of having a finished piece, a song you can share. Crucially, cultivate your community. And, in the current climate, don’t be too quick to quit your day job.

If young individuals are choosing between a formal DJ/producer education and another field of interest, I would currently advise against banking solely on a music career, unless they also possess a genuine passion and talent for building a social media presence.

If you can master that aspect, a good career is still possible. However, many truly gifted musicians are not naturally adept at social media; the required skill sets and personality traits often seem almost mutually exclusive. The most talented producers are not necessarily going to be the best influencers, and vice versa. This is a sad state of affairs because a lot of incredible talent may be lost or go unrecognized simply because these artists are uncomfortable with or unskilled at self-marketing.

How important do you think it is for safeguarding creativity by having that peace of mind through a stable job?

Having a day job or unrelated studies undeniably consumes energy that could otherwise be directed towards music. However, the alternative – trying to make a living solely from music in the current difficult climate without an established financial cushion – can be far more detrimental to creativity.

The stress of financial insecurity, the pressure of potential debt, can force you into taking on undesirable commissioned work, unfulfilling teaching roles, or churning out sample packs just to make ends meet.

It shifts your focus from long-term artistic vision and development to short-term wins. You might find yourself saying yes to small opportunities that don’t align with your larger goals, simply out of financial desperation. This pressure makes it incredibly hard to think strategically about your artistic trajectory.

For these reasons, maintaining a day job, or pursuing an education outside of music, while dedicating free time to musical development and self-education, can be a more sustainable path. It requires careful energy management, but it can provide the stability needed for genuine, long-term creative growth.

When I started, my ambition was to create art – not tools. Now, at 42, I’m beginning to feel a genuine internal urge to teach and mentor, but for young artists, the focus should ideally be on their own creative output, perhaps seeking mentorship, rather than becoming a teacher prematurely just for income.

So how important is it to really create your vision for the future early and think ahead?

I’m not the best at explicitly formulating long-term goals, and operate more as an intuitive improviser. I believe I have an internalized long-term goal that subtly influences all my decisions, but it’s not something I’ve ever clearly articulated, even to myself, let alone to others.

While explicitly defining such a vision could be very helpful for many, and probably for me too, my path to a long-term perspective has often been shaped more by a “feeling” or “vibe” that resonates, an accumulation of experiences over two decades – learning what doesn’t work through trial and error. This is what directs me to prefer creative freedom over bigger (financial) success at this point in my life.

What is success actually, then?

Ultimately, I believe the focus must always be on the long term. The idea that short-term gains, which don’t contribute to long-term fulfilment, are a poor trade-off is almost self-evidently true, yet many people still make this mistake.

This often happens because they haven’t clearly defined what they truly want in the long run. Lacking that clarity, or the wisdom that comes from making mistakes (like I have, by sometimes not prioritizing my diverse expressive needs sufficiently), they seize upon immediate opportunities, without considering their long-term implications.

I would strongly advise anyone starting out to sit down, perhaps with a mentor or someone skilled in such discussions, and honestly explore their motivations: “Why am I doing this? What do I truly want to achieve? And how does money fit into that picture?”

What are some key insights you’ve gained about the highly individual nature of the creative process and the potential harm of prescriptive “one-size-fits-all” guidance in music production?

Individual creative processes vary enormously. Take Nik (Sleepnet) and me: we share a great deal of stylistic common ground and artistic compatibility, yet our methods are vastly different.

Nik thrives on the struggle, often improving his work by relentlessly returning to it, sometimes creating 60 or more versions of a single song. He finds joy in that iterative process. I might explore six main versions, perhaps up to 24 during the mixing stage, but those later iterations are usually subtle refinements, not radical creative departures.

Nik, on the other hand, might work on a song for months and then completely discard a core element like a drop to try something entirely new. Because of such fundamental differences, I can’t offer universal advice. The best, albeit somewhat cliché, advice is to figure out what truly works for you.

I often get a bit frustrated by generic production advice I see online. It’s usually presented with great confidence, as if it’s a universal truth. But what works for one person, with their unique brain and working style, might actually hinder another’s progress by leading them away from discovering their own optimal process.

The online sphere often demands short, confident statements, but the reality of creative work is incredibly complex. When someone presents their personal method as a panacea – “This works for me, so it will work for you too!” – they’re often, unintentionally, doing a disservice to a large portion of their audience for whom that specific advice is ill-suited.

This is particularly true for advice on mindset and psychological approaches to creativity, which are deeply personal. I don’t see this complexity acknowledged nearly enough in the common discourse around production techniques.

It’s funny you say this, because basically a lot of institutionalised learning is like that, one language of learning to be used as the message

Precisely. When it comes to purely technical procedures, there might indeed be a single best way, or at least a standard way, to do something. But for psychological or mindset advice, making sweeping, confident pronouncements as if you’re a guru – and here I might gently poke at someone like Rick Rubin – can be misleading.

A particular method might have worked wonders for that individual, and for others like them, but it won’t work for everyone. By presenting it so definitively, you risk setting some people on a path that isn’t their own, potentially delaying their discovery of what genuinely works for them.

About your church organ concerts in northeast Groningen – how did this idea come about?

This project was born during the COVID lockdown, a time when I, like many, found myself excessively online, doom-scrolling, trying to distract myself from the overwhelming reality of how drastically and suddenly the world had changed. I believe many of us are still carrying unprocessed trauma from that period. It was a profoundly destabilizing event, the impact of which we are likely still underestimating.

In that context, I felt a desire to create something extremely slow, something that could serve as a tool for relaxation or focus – music to accompany studying or meditation. I envisioned a sound and texture that was inherently beautiful, offering enough musical information (in terms of notes and harmony) to be engaging if listened to attentively, yet subtle enough to be easily in the background without demanding constant attention.

The core idea was to harness the glorious texture of the church organ, complemented by cello and viola – three instruments I adore. The challenge was to set up the recording in such a way that the pure sound quality was so captivating that one could choose to immerse oneself fully in it, even though the music itself changes very little over its duration.

Mindset-wise, in preparation for these organ concerts, what really stands out for you compared to preparing for a DJ set?

The live organ performances are structured as three 45-minute sets per day, over two days. In a DJ set, if I make a mistake – and it happens constantly – I’ve learned to move past it, though I used to get quite upset.

This organ piece, however, feels much more fragile, more vulnerable. If I hit a wrong note, I fear it could shatter the intended atmosphere, break the continuity of the trance-like state I hope to induce in the audience.

These live organ concerts represent the most significant musical challenge of my life – performing live on an instrument, where even if the notes themselves aren’t technically fiendish, the sustained concentration and memory required for 45 minutes, three times a day, is immense. I said yes, and I’m hoping to navigate it without too many self-recriminations!

Beyond the mental focus, there’s a significant physical component. Playing a keyboard for that length of time, with that level of precision, engages back, core, arm, wrist, and finger muscles in a way that DJing doesn’t. It’s a physical challenge as much as a mental one. I’ll be incorporating more physical exercise – stretching, core work on my rowing machine, planking – to ensure I’m physically capable of delivering these six demanding performances.

Let’s talk about your French House ‘Le Thys’ EP

Yes, this EP is something I’ve worked on with great dedication. I pitched the initial idea to A-Trak about nine months ago, following a previous EP I did with his label. I specifically wanted to do a French House collaboration with him, but make it faster, around 140 BPM, so it fits more easily into my current DJ sets where audiences often crave higher energy.

It’s not about trying to improve upon the classic 90s/early 2000s French House sound – that era is sacred to me. Instead, it’s about recontextualising it, seeing if that vibe can work at a higher tempo, which I feel gives it a fresh twist.

One track, “The Importance of Carrots,” is actually at 160 BPM. I wrote it in a mountain house in Italy, and the track even samples an Instagram video I made there, while working on it – you can hear me eating a carrot, and the sound of the laptop speaker moving, creating a natural flanger effect, is layered into the song.

It’s these little personal, almost accidental, details that I love. The EP also features two vocal tracks. The second single, “Get Some,” is a collaboration with Daniel Bedingfield, a legend from the UK garage scene whom I met at Coachella in 2012.

We’d always talked about working together. He happened to be in Groningen, I played him my demos, he was instantly enthusiastic, and we created this track, which is very sex-positive, kinky, and BDSM-inspired. Then there’s a track like “Call Me,” which is quintessential French House in its simplicity: just a killer sampled loop with a driving kick drum, no unnecessary frills.

My love for French House goes back to the 90s, when I had Daft Punk’s Discovery on MiniDisc – it’s probably the album I’ve listened to most in my entire life. Artists like Alan Braxe, Cassius, and labels like Crydamoure and Roulé were huge influences.

Even within Noisia, tracks like “Red Heat” from our first album were heavily inspired by this sound. That was often me channelling my French House obsession within the Noisia framework. So, to finally release a dedicated project that is purely an homage to this sound, feels like a significant and proud moment, coming full circle.

You also mentioned VIER, your new ‘band’, tell us more please

VIER is a massive new chapter for me. We’ve released two songs, the next single is already lined up, and I genuinely feel this project is going to shift things for me again. Working with the other three members is incredibly intuitive, fun, and astonishingly productive.

The band consists of myself, Machinedrum, Holly, and Salvador Breed. Machinedrum and Holly had collaborated previously. They were in Groningen for an interview related to their Vision Recordings release, and the label suggested they stay a few extra days for a session with me.

We then invited Salvador, a mutual friend, who creates music and sound design for Iris van Herpen’s fashion shows (Machinedrum had also composed for one of her Paris Fashion Week shows, so they knew each other). That initial session was the genesis of VIER.

We initially joked about being “the boy band” and struggled for weeks to find a name. Eventually, I thought of “VIER,” the Dutch and German word for “four”, and it just clicked. We have an EP scheduled for release on Vision in October, and we already have enough material for at least two EPs – our productivity is almost outpacing our ability to release the music!

We keep tweaking the EP track list, because we’re constantly creating new favourites. We had our debut performance as VIER (though only with three of us, as Machinedrum couldn’t make it) at the Vision King’s Night party in Groningen.

Going forward, we’d prefer to play shows only when all four of us are available, unless it’s an absolutely unmissable opportunity. Our main focus for now, though, is to continue producing a wealth of music, hoping other DJs will play it, and we’re planning a small tour around the October EP release.

And that’s a wrap. Big thanks to Thys for making the time for this longread interview. May it provide value to those who want to become more aware of their own artistic identity and creative process.

Be sure to show some love by following, sharing, supporting his music and visiting upcoming shows.