Last year, for Black History Month, we had the privilege of speaking with some incredible artists about how bass music brands can step up and truly celebrate the genre’s deep roots in Black culture. One message stood out loud and clear: education is key. Brands should embrace the opportunity to educate new fans on the rich history of bass music and its intrinsic connection to Black culture. This year, we’re taking that advice.

We’ve teamed up with the legends at Velocity Press to bring you something special. Over the next four weeks, we’ll be presenting exclusive extracts from books that dive into this historic connection between bass music and Black culture.

Kicking things off, this week we’re exploring Join The Future: Bleep Techno and the Birth of British Bass Music by Matt Anniss. Why this book? Because it sets the scene perfectly. Anniss argues that Bleep Techno, born in 1990, was the first distinctly British form of electronic dance music—and it was powered by bass that drew directly from Black sound system culture. Ready to explore the origins of UK bass? Let’s dive in!

An Extract From Join The Future: Bleep Techno and the Birth of British Bass Music by Matt Anniss.

Chapter Three

Riddim Is Full Of Culture

Soundsystems, battles and the “blues”

“The fruits of those [interlocking social] networks are evident amongst a whole generation of young black and white people who have grown up alongside one another and shared the same streets, classrooms and youth clubs. They are visible everywhere in cross-cultural affiliations and shared leisure spaces, on the streets, around the games machine at the local chip shop, in the playgrounds and parks, through to the mixed rock and reggae groups. As a result of these, nothing is quite as “black and white” as it seems.”

Simon Jones, ‘Black Culture, White Youth’, 1988

Under overcast skies, people of all ages and ethnicities are streaming into Potternewton Park in Chapeltown. As they’ve done on each August Bank Holiday Monday since 1967, the people of Leeds are gathering to celebrate Caribbean culture at one of Britain’s oldest West Indian carnivals.

It’s early afternoon at the 2018 edition and things have yet to really get going. The sweet and sticky smell of char-grilled Jerk Chicken rises from oil barrel barbecues dotted around the park’s winding paths, while the sounds of 21st century soca, dancehall and reggae drifts over from the flatbed trucks parked up on nearby Harehills Avenue. DJs and dancers, many of whom have headed to this corner of Leeds from as far afield as Birmingham, Leicester, Manchester and Bristol, idly stand around the trucks impatiently waiting for the costumed “masquerade” parade – an annual tradition for 51 years – to finally get underway.

They’ll need to wait a little longer. Before they can take to the streets, the troupes of costumed dancers will be presented to the crowds – a mixture of stoned students, veteran ravers, proud parents pushing prams, wise old West Indian sages and crews of excitable teenagers – in front of the festival-sized main stage recently erected within the park’s natural amphitheatre.

To the untrained eye, the dancers’ dazzling, kaleidoscopic outfits are a sight to behold. Designed to be representative of aspects of Caribbean life – think birds, butterflies, animals, coral reefs and mythological characters – these colourful costumes can trace their roots back to the earliest days of Trinidadian carnival culture in the 19th century. Yet prior to Trinidad and Tobago gaining independence from Britain in 1962, carnival celebrations were condemned or outlawed in the island nation; they were, after all, anti-establishment in nature, with the associated drinking and musical merriment laced with a heavy dose of satire at the expense of the colonial authorities.

When the first wave of post-war Caribbean immigrants stepped off the HMT Empire Windrush at Tilbury Docks on June 21st 1948, they brought with them music and cultural traditions that were initially alien to their new British neighbours. With suspicion and racism rife, it would take several years before they felt comfortable enough to parade these traditions before the public, despite the presence on the passenger manifest of several leading calypso musicians (most famously Lord Kitchener, Lord Woodbine, Lord Beginner and Mona Baptiste) and Sam Beaver King, a future Mayor of Southwark who was an early enthusiast for carnival-style celebrations in London.

Over a decade would pass before these “Windrush Generation” pioneers, now settled with more friends, family and fellow islanders by their side, felt confident enough to organise community celebrations that mirrored Trinidad and Tobago’s “mas” bands and parades. There were small-scale indoor events in London from 1959 onwards, but it would take a while longer before Notting Hill’s annual outdoor carnival would be established. In fact, the first serious celebration took place in 1966, though it was a fete celebrating not just Caribbean culture but the whole of the community.

It was actually Caribbean residents of Leeds who hosted Britain’s first dedicated “West Indian Carnival” – an event organised by, and for, the city’s British Afro-Caribbean community. The groundwork was laid in 1966 when two students – Trinidadian Frankie Davis and Jamaican Tony Lewis – joined forces to put on a “West Indian Fete” at Kitson College. Twelve months later, the Leeds West Indian Carnival was born, complete with a celebratory costume parade that danced down the hill from Chapeltown to the city centre.

That first carnival was a modest affair, but by the 1980s, it had grown into a vibrant annual celebration that draws in participants – particularly dancers, steel pan bands and calypso performers – from Yorkshire, the Midlands and North West. Musical satire at the expense of the British authorities still featured, but it would be the organising committee’s 1983 decision to involve local Jamaican-style soundsystems – complete with selectors and MCs – that would shape the future of the event and better reflect the nature of the music scene within Yorkshire’s sizable West Indian community.

Today, the off-route street corner soundsystems manned by local crews attract more partygoers than the traditional parade, steel pan bands and costume competitions. You’ll find these impressive looking “sounds” rising from the overgrown front gardens of Victorian terraced houses, sitting resplendent in the middle of blocked-off side streets and – as one ingenious crew did during the 2018 edition – nestling beneath bus shelters on Chapeltown Road, the main thoroughfare that heads from Leeds City Centre up towards Hyde Park, Woodhouse and the leafy suburb of Roundhay.

The selectors and soundmen skulking behind sizable speaker stacks don’t always stick to the script passed on by their forefathers. These days, their musical selections don’t just reflect the sub-bass heavy pulse of Jamaican music but also later British styles of dance music that owe their existence to the wide-ranging cultural impact of soundsystem culture. As darkness falls, you’re just as likely to hear jungle, drum & bass, trap and grime as dub, roots reggae and lovers rock. While the rhythms and exact musical make-up differ, each of these varying expressions of soundsystem culture has one defining feature: the richness, warmth and heaviness of the bass.

• • •

The story of how soundsystem culture took root in Britain is one that’s been told many times before, with focus falling mostly on the London-based pioneers who introduced it to the UK. Yet while they provided the foundation, the culture’s spread and long-lasting influence was as much the product of those outside the capital city as within it.

According to British reggae historians, the first man to fire up a Jamaican style soundsystem – albeit a rudimentary one – in the UK was “Duke” Vincent Forbes. It was 1954 when he began playing calypso and ska records using one turntable and custom-built valve amplifiers and speaker boxes. His simple but popular system would become the blueprint for bigger, louder and more prominent sounds operated by mic-sporting reggae, rocksteady and later dub “selectors” such as Lloyd Coxsone (who began building his rig in 1962) and Jah Shaka.

London was naturally the hub of soundsystem culture in the UK during the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, but by the time the 1980s rolled around, the city’s dominance was being rivalled by similarly strong scenes elsewhere. There were notable outposts in Birmingham (clustered around the Handsworth and Aston neighbourhoods), Bristol (St Pauls and Easton), Manchester (Hulme and Moss Side), Nottingham (St Ann’s) and Liverpool (Toxteth). In fact, any town or city that boasted a significant British Afro-Caribbean community had its own soundsystems and associated events, with once mighty industrial cities, where work had been plentiful for immigrants in the first three decades after the Second World War, playing host to the most vibrant scenes.

Yorkshire’s scene was particularly strong during the ’70s and ’80s. While Chapeltown in Leeds arguably led the way, there were similarly significant communities of soundmen and selectors in Bradford (mostly in the West Bowling, Manningham and Heaton suburbs), Sheffield (Pitsmoor and Burngreave) and, most surprisingly of all for those outside the region, Huddersfield.

There, the number of custom-built sounds was, for a town of its size, surprisingly high; at its height, the town boasted over 30 systems, an astonishing figure fleshed out in delightful detail in Paul Huxtable and Mandeep Singh’s 2014 book Sound System Culture: Celebrating Huddersfield’s Soundsystems. These sounds would regularly battle against regional rivals from Sheffield, Bradford and Leeds at the local West Indian club, known as Venn Street due to its location, and at the lesser-known Aravark Club . These “sound clashes” were replicated in many other towns and cities throughout the country, with rival “soundmen”, selectors and vocalists taking it in turns to try and get the best response from the crowd.

This kind of competition was an ingrained part of soundsystem culture – a tradition that had made its way over from Jamaica, where sound clashes and battles between record-playing soundsystem operators were far more popular than concerts. It was a tradition that expressed itself in hip-hop culture in New York (thanks, in part, due to scene founder DJ Kool Herc being a Caribbean immigrant who owned his own soundsystem) and would later play a vital role in the development of numerous styles of British dance music.

Rivalry was not confined to the soundmen, either. Like the soul and electro all-dayer scenes, where dedicated dancers would battle for supremacy using jazz-dance moves, soundsystem-powered events in community centres and local Caribbean clubs also attracted competitive dancers. They didn’t breakdance or showcase their footwork moves, of course, instead choosing to style out their own take on “skanking” – a Jamaican pioneered dance that had become more widely recognised thanks to the popularity of the 2-Tone ska revival that swept Britain in the early 1980s.

Like the contemporaneous post-punk movement, this revival was the inevitable result of societal changes, most specifically, a generation of black and white teenagers who had grown up living side by side in British towns and cities. The Midlands was the birthplace of 2-Tone Records, the label that did most to popularise the sound, but there were plenty of young musical fusionists to be found elsewhere. To them, there were no boundaries and joining the dots between punk, dub reggae and American dance music made perfect sonic sense.

• • •

It would be a little longer before Bradford, Leeds and Sheffield would give birth to a futuristic new spin on soundsystem culture, though the seeds were being sown from the late 1970s onwards.

Chapeltown in Leeds may not have been able to claim the same number of soundsystems as Huddersfield, but its scene was arguably even more vibrant in the ’70s and ’80s. There, soundsystem dances and sound clashes took place in a handful of venues within the neighbourhood. “We had to do our own thing within the community,” says Mark Millington of Leeds’ leading soundsystem crew, Iration Steppas. “You couldn’t have a black dance in town, so that’s why we had the community centres to do them in, as well as certain warehouses that allowed us to do our thing with soundsystems in the ’70s and ’80s.”

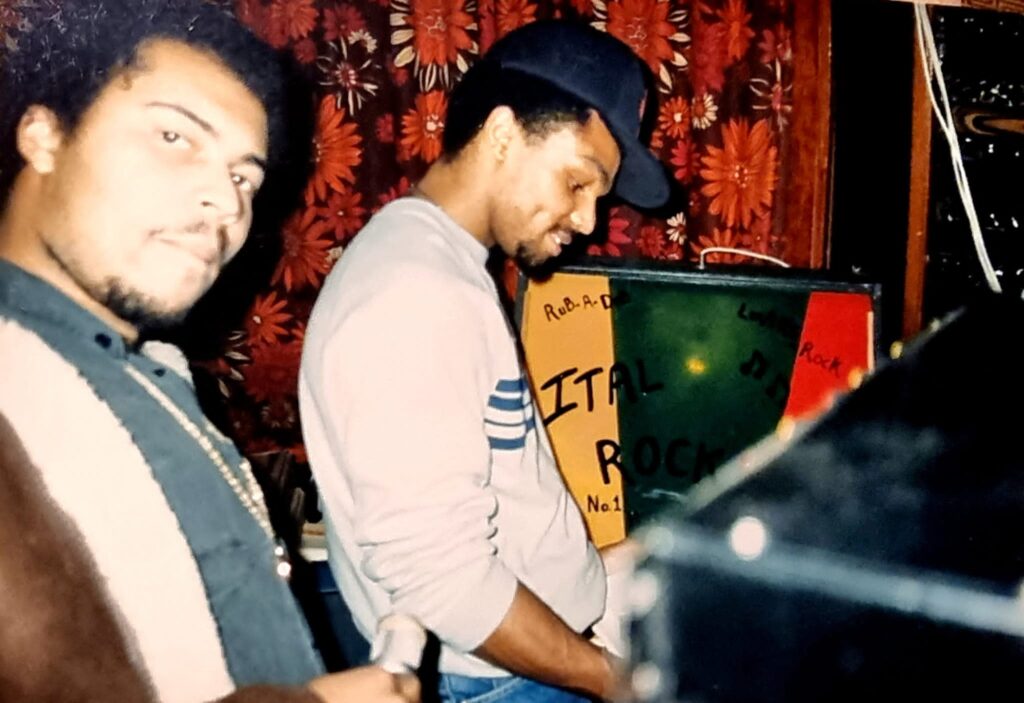

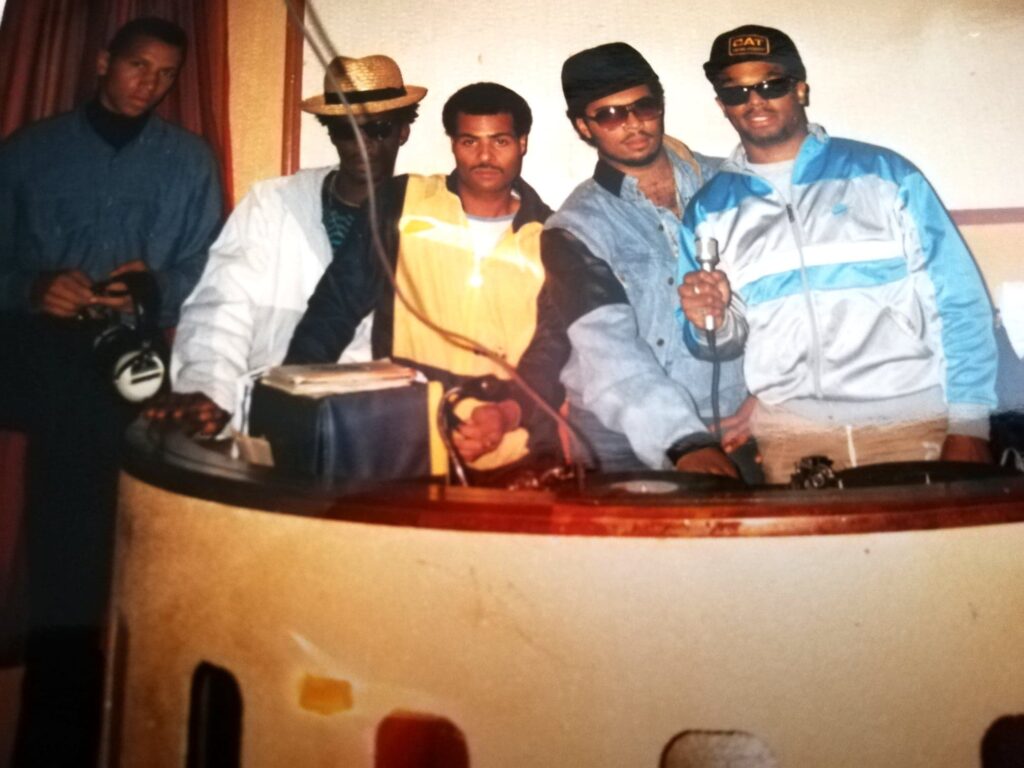

DJ on the right is Mark Millington from Ital Rockers/Iration Steppas PHOTO CREDIT: Homer Harriot

Within Chapeltown, action revolved around the Community Centre on Reginald Terrace, the West Indian Centre on Laycock Place, a former synagogue on Francis Street that was variously called the International Club and the Phoenix Club, and the Trades Hall on Chapeltown Road. Soundsystem sessions also took place in the backroom of the Hayfield Hotel off Chapeltown Road, a historic pub that was eventually demolished in the early 2000s after becoming a magnet for gang-related violence.

“There were soundsystem sessions every week at the Community Centre,” Millington explains. “We had our own local sounds who would play regularly, but there were also big events that included Jah Shaka, Tubby, Saxon and even Coxsone – many sounds from out of town that people might know played there. When they got bigger, Saxon would play the Community Centre on their own without someone like Shaka also being on the bill. Those sessions were roadblock!”

In the Jamaican tradition, each soundsystem would have its own specific musical niche. Some would be light and soulful, showcasing roots reggae or lovers rock (Kooler Ruler, one of the first sounds to play at Leeds West Indian Carnival in 1983, led the way locally in this regard), while others would prioritise the bass-weight and heavy dancefloor rhythms of dub. Key Leeds sounds at the time included Chapeltown-based Ambassador, Genesis, Magnum 45, Ras Claart, Emperor and Jungle Warrior, as well as Mess-I and Messiah from Hyde Park (an area better known for its student population but also host to British Afro-Caribbeans thanks to its proximity to Chapeltown and Harehills).

“The North was quite strong in the ’70s and ’80s for dub,” Millington remembers. “Leeds was mainly a dub town at that time. The Community Centre in Chapeltown was the big thing at the time, but Venn Street in Huddersfield and Palm Cove in Bradford were also important. It was like a circuit – something would be happening every weekend at one of those places and you went there to support the dances. We were very entertained and that’s where we got our inspirations from.”

The circuit, as Millington describes it, also included Bensons and Checkpoint in Bradford, where he’d later DJ on Sundays, occasionally with his cousin’s local sound, Conquering Lion. Like a lot of local soundsystem DJs, Millington got his records from what has become a Leeds institution: Sir Yank’s record shop on Gathorne Road. A tiny, ramshackle place run out of a tiny building at the back of a row of back-to-back terraced houses, Sir Yank’s has somehow survived to this day.

“It was the main Jamaican import place at the time,” Millington explains. “Sir Yank had a garage and used to sell out of that, or his house. I’d go to Sir Yank’s straight from school and stand outside hearing music play. If you liked a certain record he put on, you’d stick your hand up and be like, ‘Yeah! I want one of these!’ Sometimes he’d have ten copies of something, sometimes one, so you had to be there to grab one or they’d all be gone. It was a great place to meet and listen to music.”

• • •

Sir Yank’s customers were not only the soundmen and selectors who lugged their heavy equipment down to local community centres for evening dances, but also those whose sounds resided in the ‘blues’ – unlicensed, all-night social clubs located in the backrooms and basements of residential houses within Chapeltown and Hyde Park.

“There were so many blues – I think Leeds had more than London at that time,” Mark Millington says. “They were all around the streets of Chapeltown. They had local sounds and DJs, but some also brought in sounds from out of town on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays.”

Blues, or ‘shebeens’ as they’d previously been called, first emerged within the Caribbean communities of major British cities in the 1950s. They were much-needed safe social spaces where community members could gather, listen to music, dance and play cards or dominoes. In an era where regular pubs and clubs could be no-go areas, they provided an essential service for the communities they served.

“I think that was one of the reasons it was allowed to go on,” says George Evelyn, then a Hyde Park teenager who maintained an interest in dub and reggae music despite his devotion to breakdancing. “As long as the Blues were there, the police knew where everybody was. If it’s self-contained in a few places in one neighbourhood, it’s easier to control. It kept things under wraps to an extent because there was somewhere for people to go. People were occupied and entertained.”

Due to their illicit, word-of-mouth nature, blues came and went on a regular basis. “It was an open thing – anyone could do a blues,” Mark Millington says. “Once you had drinks, music and the authority of the property owner to run that Blues, it was no big thing. Anyone could run them and lots of people did.”

More often than not, blues were named after their proprietor, a member of the local community with an interest in soundsystem culture and an entrepreneurial spirit. In Chapeltown, that meant Blues with names like Duke’s, Cliff’s, Maxi’s, Sonny’s and Streeger’s; in Sheffield, it was CJ’s, Pinky’s, Mandeville’s, Brace’s, Chatoo’s (held in a prefab building in the back garden of a terraced house off Chesterfield Road) and the most famous of all, Donkey Man’s.

These infamous owners would often work the door, leaving hosting and bar duties to a strong female member of their family. Each blues would boast a soundsystem, which had either been built specifically for the space or was carried in for each all-night session. There would usually be a small homemade bar selling a limited range of drinks (think rum, Red Stripe beer and Coca-Cola) and occasionally a kitchen dishing up traditional Jamaican food. Entrance was at the discretion of the owner and was usually via a side door or backdoor. Crucially, the Blues often opened at 2am, around the time when city centre clubs were closing and went on through the night.

“Some of the blues, like Darkies near Sir Yank’s, would take up most of a house, while others were just the ground floor or cellar,” remembers Gip Dammone, then an aspiring promoter of jazz-dance clubs (he would later go on to be a successful restaurateur and club owner). “There were lots of blues in Chapeltown around that time [in the mid-1980s] and it was mostly reggae music you’d hear. You’d see lovely, incongruous things, like all these dreads hanging out and then two little women sat to the side drinking Babycham at six in the morning. There would be all sorts of people in there – they were like social clubs.”

Dammone, a white Yorkshireman of Italian heritage, regularly visited blues alongside other workers from the restaurant, club and pub trade. “In the 1970s and ‘80s the whole Leeds restaurant trade would go to Chapeltown after work because it was safer,” he says. “We were a bit scared of going into town after work – there was a lot of violence. For the most part, I found it friendly in Chapeltown in those days. It had quite a vibrant scene.”

Aside from Dammone and his colleagues, the blues were also a draw for members of the music community. “When I lived in Wakefield, I’d travel over to Chapeltown or Bradford to the blues quite a lot,” says Leeds promoter Dave Beer, one of the key figures behind the city’s long-running Back To Basics club night. “The Blues were the only place you could buy weed. It could be dangerous territory sometimes and you had to have big balls as a skinny white kid to go down there.”

It was a similar story down the M1 in Sheffield, whose post-punk “industrial funk” musicians regularly headed to the Blues after gigs or studio sessions. “Some members of the band were constantly at Donkey Man’s blues,” says producer and former Moloko member Mark Brydon who, at that point in the 1980s, was riding high as a member of Steel City band Chakk. “I always found it very friendly. We used to knock on the door and ask whether we could come in. I used to spend evenings with my head in the bassbins of their big soundsystem listening to proper roots rock dub reggae. There was no bother – nobody hassled us, and we could have a draw and listen to music.”

Brydon and his Chakk bandmates shared a house close to another notorious blues, CJ’s in Broomhall. “It wasn’t somewhere you’d go regularly,” Brydon says with a smile. “It was somewhere you felt privileged to be allowed in. It was probably the fact that our faces were seen so much around the neighbourhood that got us in. I think going to Donkey Man’s and CJ’s definitely informed the way that our records sounded because we learned so much about good bass and bad bass from those Blues. It’s true that the blues really influenced the way records were being made.”

The outlaw nature of the blues, which often switched location from one house to another on the rare occasions that the police decided to take an interest in their activities, did scare off some potential attendees, though not Brydon or Leeds’ Gip Damone and his friend DJ Lubi.

“I remember one night I was in Darkie’s with my brother Simone and we got into some trouble for roaching up this fag packet that we thought someone had discarded on the pool table,” Dammone says. “So, we’re smoking this joint and a guy appears – he looked like a general, with square shoulders on his jacket. He was carrying a cane. He was giving us the evil eye and started talking to us aggressively because it turned out we’d ripped up his cigarette packet. We knew the cook, so he took him into the kitchen and had a word. When he came back out again, he was all smiles, but we passed him the spliff and scarpered.”

That was not the only occasion that Dammone had to flee a blues in a hurry. “Another time, a guy came into the blues that Simone and I were in wielding a cutlass,” he laughs. “I got out of there pretty quickly and ran like fuck!”

• • •

By the mid-1980s, the musical purity of the blues as a haven for roots, dub and reggae was beginning to be challenged by a new generation of DJs and dancers. While some loved reggae, others were more excited by the potential of jazz-funk and emerging styles of American dance music, such as electro, hip-hop and house.

“I remember one time at Darkie’s, where a jazz dancer called Doville had arranged for Manchester DJ Hewan Clarke to play,” DJ Lubi remembers. “Hewan was already there when we walked into the basement, which was lit by red lights at either end of the room. Hewan was standing there in the DJ booth, which was encased in wire mesh. They must have got two turntables in for that one because they normally had one. Hewan played everything – soul, rare groove, electro, jazz-funk and reggae. We were meant to play but just got some beers and stood next to him in the DJ booth. A few looked at us suspiciously, but it was fine because we were with the DJ.”

Events like this were still a rarity, though, and it would take the efforts of a young DJ with ambitions to build his own soundsystem to really change things. This was Mark Millington, who along with his friend Sam Mason was well known for wandering around the neighbourhood with a “sound” made out of two connected ghetto blasters.

“Everybody knew me as Music Man,” Millington says with a chuckle. “Me and Sam would always be walking around with our ghetto blasters. People said to me, ‘why don’t you build your own sound?’ I’d say, ‘I can’t be arsed because it costs money and I’m on the dole’. Eventually, I was persuaded to do it and that turned out all right.”

Ital Rockers PHOTO CREDIT: Homer Harriot

It would take a while before that sound, Ital Rockers, would be built. By that time Millington was a respected DJ with a Sunday residency at Checkpoint in Bradford – assisted by an older local reggae musician and wannabe producer Homer Harriott. “When we played at Checkpoint, I used to play soul mainly,” Harriott says. “When house came in from Chicago, Mark started buying those records. Before we played as Ital Rockers at the community centre, it had always just been reggae on those Sunday sessions, but we changed that.”

By early 1987, Millington had started building what would become the Ital Rockers soundsystem. “It was never a major sound,” Harriott says. “It was a cross between a home hi-fi and a soundsystem. It had big [speaker] boxes, but they weren’t as big as a regular soundsystem’s boxes. Musically Mark was talented and could compete on the strength of his selections, but at that time not on the strength of his sound.”

The Ital Rockers soundsystem soon became a regular sight in venues around Chapeltown, particularly the Hayfield Hotel, the Trades Club and the community centre on Reginald Terrace. While Millington would stick to reggae – and dub specifically – at some gigs, he was just as excited by the possibilities offered by the new American styles of house and techno, which he saw as some futuristic form of dub.

“Ital Rockers was a party sound – I played everything,” Millington asserts. “That meant lovers, house, garage, soul, hip-hop, reggae, dancehall and dub. I did this thing once a month at the Hayfield Hotel with my little soundsystem. I’d be playing dub and dancehall, then get on the mic and say, ‘We’re switching’. I’d then play house and stuff like that.”

Not all of the drinkers at the Hayfield Hotel were that keen on Millington’s desire to mix up the sounds they were hearing. “I took a lot of flak,” he says. “Man would say: ‘take that shit off’ and ‘keep to rub-a-dub!’ There was a sound at the time called Jungle Warrior and their soundmen and DJs were often at the Hayfield when I was playing. As soon as I started playing house they’d leave or go outside, then the dancers who wanted to hear that sound would come in. The Jungle Warrior guys hated house and hip-hop, but later down the line they embraced it. It took a lot of people years to realise that to be a DJ you had to be versatile in what you played.”

Millington was a trailblazer in Leeds, but he was not alone. There were others across Yorkshire committed to mixing up styles, though they were more often found DJing in regular clubs than in community centres and blues. “For some reason, I didn’t give a fuck,” Millington says. “I believed in what I was doing. A lot of people tried to drag me back to just playing reggae but I stuck to my guns. I’m proud of myself when I look back on it. I can say that I created a pathway for a lot of people. The dub scene has now had evolutions through the introduction of house and hip-hop influences.”

To the west in Bradford, another DJ crew – one without a soundsystem of their own – was making waves. Formed by Ian Park and cousins Patrick Cargill and Kevin ‘Boy Wonder’ Harper during their time in breakdance crew Solar City Rockers, Unique Three were renowned for mixing up hip-hop, electro, jazz-funk, reggae, dub and house. They played regularly at local community venues such as Checkpoint and Benson’s, building a decent following among dedicated dancers and regular punters.

“Unique Three was a big name coming out of Bradford at the time,” Millington remembers. “They played really good music. People were saying things to us like, ‘Unique Three think that they can kill Ital Rockers!’ It was this big Bradford and Leeds rivalry I suppose.”

The rivalry was such that Unique Three decided to challenge Millington and the Ital Rockers crew to a sound clash, an old-fashioned soundsystem style battle for supremacy, at a club on Manningham Lane in Bradford. “It wasn’t a big deal at first, but the closer it got, the bigger it became,” Millington grins. “We took it really seriously.”

So seriously, in fact, that Millington enlisted the help of Homer Harriott to create some “specials” – exclusive tunes that would never leave his collection, like the dubplates cut for leading soundsystem DJs in Jamaica – to try and best their Bradford rivals.

“I’d just started putting a little studio together with a TEAC four-track, a Yamaha drum machine, a Juno 106 synthesiser and some other little bits of gear,” Harriott remembers. “Mark, our mate Maz and me could all sing so we’d get on the mic as well. We started making little dub versions of tracks like you would for a reggae dance, but in a house style.”

These ‘specials’ were largely covers of popular house tracks, with new lyrics and vocals making fun of their West Yorkshire rivals. “One of them was a cover of Hercules’ ‘Seven Ways To Jack’,” Harriott says. “We included us singing lyrics that said what we were going to do to Unique Three. So, ‘Seven Ways to Jack’ became ‘Seven Ways to Destroy Unique Three’. Like, ‘Number one, go in the studio. Number two, create some dubplates’. Near the end of the dance, we’d always want to end with a bang, so we’d have a few “specials” to drop. That’s where I started to get more interested in making dance music.”

When it came to the overhyped sound clash in Bradford, those ‘specials’ did the business. The set-up of the clash, which took place in the autumn of 1987, featured Unique Three at one end of the room using the house system, with Millington and Harriott on the Ital Rockers soundsystem at the other.

“We killed them at that clash,” Millington laughs. “I remember that ‘Seven Ways To Kill Unique Three’ kicked up the place – it went crazy! There was another one we did called ‘Ital Rockers In The House’ and that went down really well. People still ask me for that tune to this day. The thing is, Unique Three didn’t prepare for that clash like we did. I was the soundman in them days so I knew about dubplates and clashes. We went there as if it was a real soundsystem clash and they turned up with just their latest tunes from Chicago or whatever. Having stuff from Chicago didn’t mean jack shit when we had dubplates!”

It was a sign of things to come. Twelve months later, Unique Three would respond in the best possible way by unleashing a thunderously bass-heavy record that set the ball rolling on Britain’s bleep and bass revolution. It was a challenge that Millington, Harriott and many others in Sheffield, Leeds and Bradford simply couldn’t resist.