“I’ve been really happy about how people within the jungle scene have been able to continue to grow to where now they’re able to target people outside of their scene. I see that as a natural progression for our music, to continue to grow to a point where people outside of our circle can no longer ignore us and take notice now.” – Tim Reaper

Crunchy, syncopated breakbeats, soundsystem-rattling 808s and a plethora of well-sourced samples. The foundations of jungle are to many rooted sonically with these three unassuming elements. To some, the word jungle is a hazy trip back in time to Metalheadz’ infamous Blue Note Sessions, or to smoke-filled dancefloors of the seminal Jungle Fever raves. To others, it’s sat at home listening to the latest Western Lore release, or raving with the regulars at Rupture in Corsica Studios.

Like any genre, the music has evolved with the times, and technology has as much a part to play as the constantly shifting audience and surrounding political/social climates. However, these musical elements remain at the forefront, and there is a craving for that 90s sound that sticks with even the newest of jungle releases. Names like Dillinja, Ray Keith, LTJ Bukem and Peshay (to name a mere few) are often linked with the adored jungle sound, and their early efforts still have an impact on the music today.

If you listen to drum and bass then I have to break it to you .. you’re listening to jungle .. ok

— GROOVERIDER (@GROOVERIDERDJ) December 12, 2020

In recent years, however, there has been a steady resurgence of the jungle and hardcore sounds that we associate at large with the 90s. Perhaps resurgence is not the right word here, as the sound never truly left. But the appreciation in wider circles of music seems to be constantly rising, along with the list of thriving new jungle producers. Artists that are constantly reinventing the wheel today include the likes of Coco Bryce, Tim Reaper, Pete Cannon, Sully, FFF, Kid Lib and Dead Man’s Chest.

In his recent book Bass, Mids, Tops writer Joe Muggs describes all of underground and soundsystem music as being “hyper-social – formed from interlocking networks of crews and movements, each one comprised of individuals whose cultural perspective is formed from thousands of hours immersed in crowds, sounds, words and bass.”

Within this article I speak to Coco Bryce, Tim Reaper and Pete Cannon about their personal experiences with jungle, and this ‘hyper-social’ idea holds true, each with diverse, individual stories that shape their own understanding and experience of the genre.

Labels like Lobster Theremin, largely thought of as sitting firmly in the lo-fi house and techno scenes, have even been key in pushing this sound to wider audiences. It’s not hard to see why, with tunes like Coco Bryce’s Ma Bae Be Luv fitting this lo-fi aesthetic with its rough and ready breaks, melancholic nature and club/home listening adaptability. It highlights a new streamability to the genre, far away from the days of white labels and bargain bins – yet the sound remains in many ways unscathed.

“I think maybe just the 90s influence has more appeal than some of the modern stuff that drum and bass is putting out,” Tim Reaper says to me regarding his recent releases on Lobster Theremin and the appreciation of jungle in house and techno circles. In fact, there seems to be a sort of romanticised idea about jungle here, with it not being uncommon to hear a techno DJ dropping a jungle tune in a set, yet drum and bass here often feels far less drawn for.

Even within drum and bass, the meaning of ‘jungle’ can also often get lost, and to newer faces to the scene it can seem confusing. It could seem apparent that drum and bass with a ragga vocal is ‘jungle’ to the uninitiated, or perhaps it could just be a term used interchangeably with drum and bass.

“The thing with jungle is it’s really open to interpretation” Tim explains to me. “To some people it’s just a vibe, to some people it’s a certain set of sounds, or how those sounds are used. For me when I say jungle, I usually think of the 93-95/96 era, and anything that tries to replicate that authentically.”

New-school jungle mainstay Coco Bryce explains to me how jungle never quite reached the Netherlands in the same way as it did in the UK, and instead he grew up with gabba and hardcore as his “fast music”. Through the lens of hardcore, he and his friends immersed themselves in the music, soon learning to DJ and exploring labels like UK hardcore imprint Kniteforce Records. It was labels like this, heavily utilising breakbeats in each release, that led to him eventually discovering jungle with the help of a feature on a Dutch radio station.

The pandemic has hardly halted Coco Bryce’s output. In fact, the opposite could be said, as he explains to me that he’s never sold as many records as he did last year. One of the more surprising releases of these was the Hold The Line EP on Critical Music. Headed up by Kasra, Critical have firmly established themselves as one of the mainstays for modern drum and bass, yet the link up with Coco Bryce and his take on 90s jungle sounds proved this appreciation for the music runs deep. “It was quite surprising for me, but at the same time not really,” he continues, citing previous jungle inspired releases on the imprint from the likes of Sam Binga.

“A lot of people were really surprised, but I’ve had nothing but good reactions to it. The only reactions that I see are from people that are already following me on social media. I definitely did see – especially with Lobster but also with Critical – that as soon as I released stuff on those labels, I got a very different following on social media. You see a lot of people start to follow you that are from a slightly different crowd from the people that followed you before.”

It is plain to see that despite the obvious and direct connection between the two genres, there is still often a divide between the crowds, and possibly often confusion at play. “It does feel a little separate,” Pete states to me, sounding deep in thought. “However, Hospital have got the rooms at events where they’re putting on people like Coco, Tim and myself, so it’s still bubbling… Say a 19 or 20-year-old kid who’s never even delved into the older jungle hears some new stuff from us lot, they might then look into the history of it. It’s great for that.”

Perhaps the central element to the genre and electronic music at large is that of the breakbeat itself, holding an almost mythical status among music heads. There is no jungle without the plethora of sampled breakbeats in existence, it sits at its very core. Pete Cannon is a producer and music head whose enthusiasm for jungle is admirable, and he relishes the opportunity to talk in depth about sampling, hardware and his deep respect for the genre. “I come from a hip-hop background so sampling and digging – looking for drum breaks and different sounds – is part of what I do and what I like doing.”

“With jungle”, he continues. “There are so many different angles on it that span from 93-97. There’s the Tom & Jerry soul stuff, The ruff ragga 94 vibe, soulful Wax Doctor stuff, Dillinja, Photek. It goes on. There’s a huge scope to it because more of a breadth of music was being sampled.”

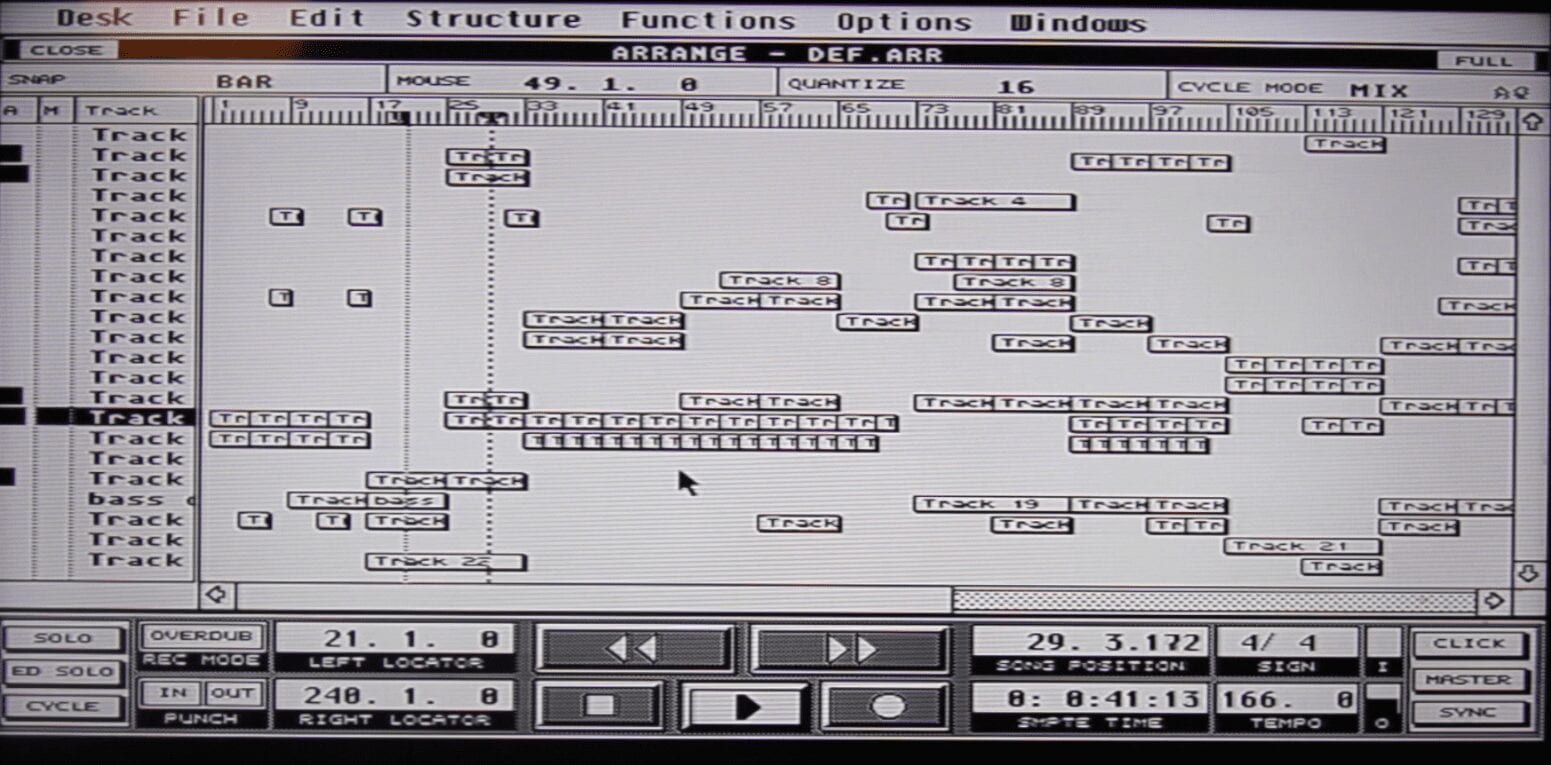

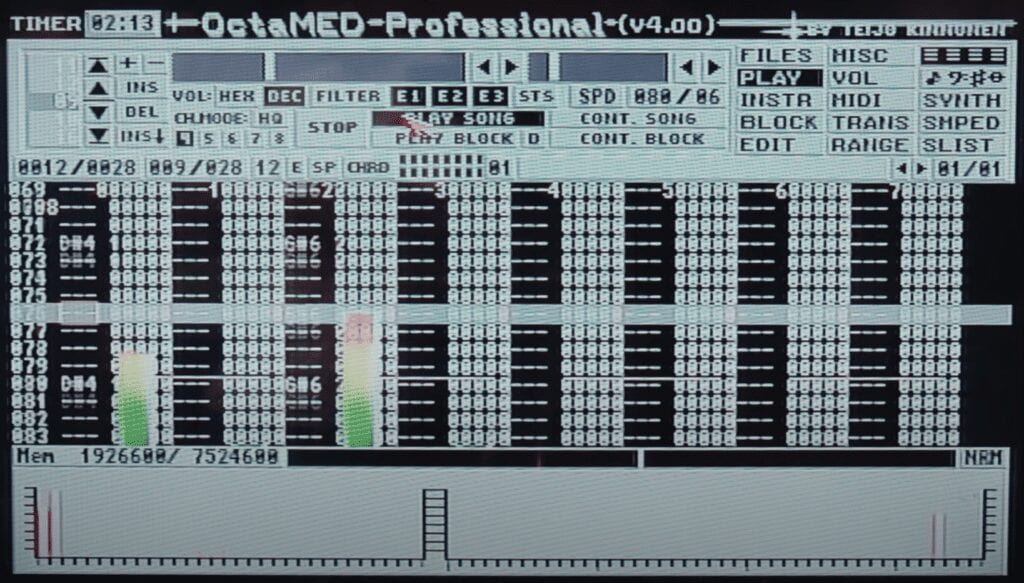

In similar fashion to Coco Bryce, Pete discovered his love for the music through rave CDs and tapes, before eventually finding an independent record shop in Blackpool at which he bought his first record, the iconic warping sounds of Dead Dred’s Dred Bass in 94. From there, a deep fascination with sampling and the culture of jungle immersed him, and now you can find him posting in Facebook groups like Long Live Beautifully Crafted Jungle, with quick dives into his hardcore and jungle tracks – often made on now ancient equipment like the AKAI S950 sampler, his treasured Amiga computer and OctaMED software.

“I wanted to go through the original process that people were doing in the mid 90s making jungle,” he explains. “I’ve kind of done it with the Amiga on its own with the 8bit samples, but then now adding the sampler to it and understanding the MIDI and the outboard synths. It was just something I wanted to do. I love the music so much, it’s my life.”

He goes on to stress that there is no snobbery here: “It’s what comes out the speakers man, it’s whatever helps you in the process. I like to enjoy making music, it’s whatever helps you gets you to the end. It ain’t nothing if you’re using a 950 or not.”

Chatting to Coco Bryce and Tim Reaper on the matter, they both discuss their experience with producing jungle in relation to sampling and their lack of reliance on hardware. “It’s just about where you source your samples from,” Tim explains to me. “It’s how you treat and process them, and what you do with them.”

Coco Bryce shares the same sentiment: “I think it’s about the sample sources. If you use raw samples that came from old hardware, then it’s automatically going to have a similar vibe to it.” He also mentions how other genres can be largely focused on mixdowns, a term that refers to the balancing of each individual element to create a final track to be sent off for mastering. Jungle, however, is very much focused on the vibe first and foremost, at large due to the general aesthetic of the music being directly linked with the technical limitations that gave birth to its sound.

On the topic of mixdowns in electronic music, Pete explains “you want to be at a level, don’t you? But also, I think jungle doesn’t have to be pushed as much. I’m not a huge fan of overly transient shaped drums that are maxed out. Of course, there is a fine line because you want something to smack in a club.”

It is important to note here that these three are needles in a haystack of new-school jungle talent, yet what is quickly apparent is their shared enthusiasm when talking about the genre. Whether it’s the history of the samples or its complex history rooted in soundsystem culture, there is a fascination with the genre that listeners, ravers and producers seemingly immerse themselves in the moment they first hear those booming 808s and chopped up breakbeats.

All the conversations come back to the idea that they are doing this music for themselves first and foremost. It is an art and lifestyle that they want to attach themselves to for their whole career, and it makes sense why the music has stayed so true to its core in terms of sound and aesthetic. It’s a respect for the music that naturally runs deep thanks to its very core musical DNA, and it’s an idea and philosophy we should all try and incorporate into all corners of electronic music.

Amen to this: Coco Bryce, Tim Reaper and Pete Cannon on their favourite breaks…

Coco Bryce: “That’s impossible man… I can give you my favourite combination. I’ve used this one a million times and that’s the Soul Pride with the Think break. I should stop using that combination, but I can’t stop, they just sound so good together. One is all high and crispy with the tambourines and shakers, and then the Soul Pride is clunky and woody sounding. Together they are just this perfect mash-up to me.”

Tim Reaper: “You know, I don’t actually use it that often, but I’d say the Cold Sweat break. As much as the Amen is great and some of my favourite tunes on this shelf right now are Amen tunes, I just feel that the Cold Sweat is a proper underrated breakbeat with a nice snappy snare and good rides. It’s good for layering and it stands up on its own weight, and it doesn’t get much shine these days because everyone likes the Amen, Think, Sesame Street, Helicopter and all those kinds of breaks.”

Pete Cannon: “I could definitely say something obscure or rare, but let’s get it right… the Amen break. There are so many variations of it including all the 2nd generation versions. There’s an Amen break that’s famously used from an early 90s UK hip-hop crew which is on the Peshay stuff like Gangsta. Apache as well, you’ve got to love that haven’t you. The two go well together. Or maybe the Fast Eddie break, that’s killer.”

Follow Tim Reaper | Coco Bryce | Pete Cannon